what services did the freedmens bureau offer to southerners

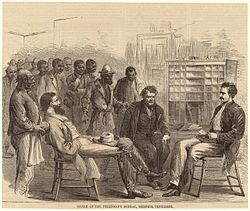

A Bureau amanuensis stands between a grouping of whites and a group of freedmen. Harper's Weekly, July 25, 1868.

The Agency of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abased Lands, commonly referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau,[1] was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March iii, 1865, and operated briefly as a U.S. government agency, from 1865 to 1872, after the American Civil War, to directly "provisions, article of clothing, and fuel...for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children".[ii]

Groundwork and operations [edit]

In 1863, the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission was established. Ii years later, as a result of the enquiry[3] [iv] the Freedmen's Agency Bill was passed, which established the Freedmen's Bureau as initiated by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. Information technology was intended to last for one year after the stop of the Ceremonious War.[5] The Agency became a function of the United States Section of War, as Congress provided no funding for it. The State of war Department was the only agency with funds the Freedmen's Bureau could use and with an existing presence in the Due south.

Headed by Spousal relationship Army General Oliver O. Howard, the Bureau started operations in 1865. From the outset its representatives found its tasks very difficult, partly considering Southern legislatures passed Black Codes that restricted move, conditions of labor, and other ceremonious rights of African Americans, almost duplicating atmospheric condition of slavery. Also, the Freedmen's Bureau controlled only a limited amount of arable state.[half dozen]

The Bureau's powers were expanded[ past whom? ] to assist African Americans observe family members[ how? ] from whom they had become separated during the war. Information technology arranged to teach them to read and write—skills considered critical by the freedmen themselves besides equally by the government.[seven] Bureau agents also served as legal advocates for African Americans in both state and federal courts, mostly in cases dealing with family bug.[7] The Bureau encouraged former major planters to rebuild their plantations and pay wages to their formerly-enslaved workers. Information technology kept an eye on contracts between the newly-gratis laborers and planters, since few freedmen could read, and pushed whites and blacks to work together in a free-labor market as employers and employees rather than every bit masters and slaves.[7]

In 1866 Congress renewed the charter for the Agency. President Andrew Johnson, a Southern Democrat who had succeeded to the office following Lincoln's assassination[8] in 1865, vetoed the pecker, arguing that the Bureau encroached on states' rights, relied inappropriately on the armed services in peacetime, gave blacks assistance that poor whites had never had, and would ultimately prevent freed slaves from becoming cocky sufficient by rendering them dependent on public assistance.[5] [nine] Though the Republican controlled Congress, overrode Johnson's veto, by 1869 Southern Democrats in Congress had deprived the Bureau of about of its funding[ how? ], and as a outcome it had to cutting much of its staff.[v] [x] Past 1870 the Bureau had been weakened further due to the rise of Ku Klux Klan (KKK) violence across the South; members of the KKK and other terrorist organizations, attacked both blacks and sympathetic white Republicans, including teachers.[5] Northern Democrats as well opposed the Agency'south work, painting it every bit a program that would make African Americans "lazy".[11]

In 1872 Congress abruptly abandoned the plan, refusing to approve renewal legislation. It did not inform Howard, whom U.S. President Ulysses Southward. Grant had transferred to Arizona to settle hostilities between the Apache and settlers. Grant'south Secretary of War William West. Belknap was hostile to Howard'south leadership and authority at the Bureau. Belknap aroused controversy amongst Republicans past his reassignment of Howard.[ citation needed ]

Achievements [edit]

24-hour interval-to-mean solar day duties [edit]

The Freedmen'south Agency office in Memphis, Tennessee, 1866.

The Bureau mission was to aid solve everyday problems of the newly freed slaves, such as obtaining food, medical care, communication with family members, and jobs. Between 1865 and 1869, information technology distributed 15 one thousand thousand rations of food to freed African Americans and five million rations to impoverished whites,[12] and set up a arrangement by which planters could borrow rations in order to feed freedmen they employed. Although the Agency set aside $350,000 for this latter service, merely $35,000 (10%) was borrowed by planters.[ commendation needed ]

The Agency's humanitarian efforts had express success. Medical treatment of the freedmen was severely deficient,[thirteen] as few Southern doctors, all of whom were white, would care for them. Much infrastructure had been destroyed by the war, and people had few means of improving sanitation. Blacks had piffling opportunity to become medical personnel. Travelers unknowingly carried epidemics of cholera and yellow fever forth the river corridors, which broke out across the Due south and acquired many fatalities, especially among the poor.

Gender roles [edit]

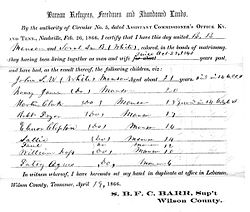

A certificate of marriage issued by the Freedmen'due south Bureau

Freedman's Bureau agents initially complained that freedwomen were refusing to contract their labor. One of the first deportment blackness families took for independence was to withdraw women's labor from fieldwork. The Bureau attempted to force freedwomen to piece of work by insisting that their husbands sign contracts making the whole family bachelor as field labor in the cotton industry, and past declaring that unemployed freedwomen should be treated every bit vagrants just as blackness men were.[fourteen] The Bureau did allow some exceptions, such as married women with employed husbands, and some "worthy" women who had been widowed or abased and had big families of pocket-size children to care for. "Unworthy" women, significant the unruly and prostitutes, were usually the ones subjected to punishment for vagrancy.[fifteen]

Earlier the Ceremonious War the enslaved could not ally legally, and virtually marriages had been informal, although planters oftentimes presided over "wedlock" ceremonies for their enslaved.[ commendation needed ] Later on the war, the Freedmen's Bureau performed numerous marriages for freed couples who asked for information technology. As many husbands, wives, and children had been forcibly separated nether slavery, the Bureau agents helped families reunite later the war. The Bureau had an breezy regional communications system that allowed agents to send inquiries and provide answers. Information technology sometimes provided transportation to reunite families. Freedmen and freedwomen turned to the Agency for assistance in resolving issues of abandonment and divorce.

Educational activity [edit]

The almost widely recognized accomplishments of the Freedman's Bureau were in teaching. Prior to the Civil State of war, no Southern state had a arrangement of universal, state-supported public teaching; in addition, most had prohibited both enslaved and free blacks from gaining an education. This meant learning to read and write, and do simple arithmetics. Former slaves wanted public educational activity while the wealthier whites opposed the thought. Freedmen had a potent desire to larn to read and write; some had already started schools at refugee camps; others worked hard to establish schools in their communities fifty-fifty prior to the advent of the Freedmen'south Bureau.

Oliver Otis Howard was appointed every bit the first Freedmen'south Bureau Commissioner. Through his leadership, the bureau set up iv divisions: Government-Controlled Lands, Records, Financial Affairs, and Medical Diplomacy. Education was considered part of the Records division. Howard turned over confiscated property including planters' mansions, regime buildings, books, and furniture to superintendents to be used in the education of freedmen. He provided transportation and room and board for teachers. Many Northerners came due south to brainwash freedmen.

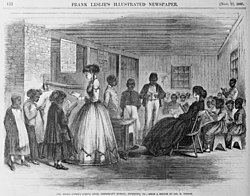

The Misses Cooke'southward school room, Freedmen's Agency, Richmond, Virginia, 1866.

By 1866, Northern missionary and aid societies worked in conjunction with the Freedmen's Bureau to provide didactics for former slaves. The American Missionary Association was particularly active, establishing eleven "colleges"[ which? ] in Southern states for the didactics of freedmen. The chief focus of these groups was to raise funds to pay teachers and manage schools, while the secondary focus was the day-to-day functioning of individual schools. After 1866, Congress appropriated some funds to operate the freedmen's schools. The primary source of educational acquirement for these schools came through a Congressional Deed that gave the Freedmen's Bureau the power to seize Amalgamated property for educational use.

George Blood-red, an African American, served equally a teacher and school administrator and as a traveling inspector for the Bureau, observing local weather, aiding in the establishment of black schools, and evaluating the performance of Bureau field officers. Blacks supported him, but planters and other whites opposed him.[16]

Freedmen's Schoolhouse, James Plantation, North Carolina

Overall, the Bureau spent $5 million to set up schools for blacks. By the cease of 1865, more ninety,000 former slaves were enrolled as students in such public schools. Attendance rates at the new schools for freedmen were about fourscore%.[ citation needed ] Brigadier General Samuel Chapman Armstrong created and led Hampton Normal and Agricultural Found in Virginia in 1868. It is now known as Hampton University.

The Freedmen's Agency published their ain freedmen's textbook. They emphasized the bootstrap philosophy, encouraging freedmen to believe that each person had the ability to piece of work hard and to do meliorate in life.[ description needed ] These readers included traditional literacy lessons, as well equally selections on the life and works of Abraham Lincoln, excerpts from the Bible focused on forgiveness, biographies of famous African Americans[ who? ] with emphasis on their piety, humbleness, and industry; and essays on humility, the work ethic, temperance, loving your enemies, and avoiding bitterness.[17]

By 1870, there were more 1,000 schools for freedmen in the South.[xviii] J. W. Alvord, an inspector for the Bureau, wrote that the freedmen "take the natural thirst for knowledge," aspire to "power and influence … coupled with learning," and are excited by "the special study of books." Amongst the former slaves, both children and adults sought this new opportunity to learn. Later the Bureau was abolished, some of its achievements collapsed under the weight of white violence confronting schools and teachers for blacks. Virtually Reconstruction-era legislatures had established public pedagogy but, after the 1870s, when white Democrats regained power of Southern governments, they reduced funds available to fund public education, especially for blacks. Beginning in 1890 in Mississippi, Democratic-dominated legislatures in the South passed new state constitutions disenfranchising most blacks by creating barriers to voter registration. They then passed Jim Crow laws establishing legal segregation of public places. Segregated schools and other services for blacks were consistently underfunded by the Southern legislatures.[19]

By 1871, Northerners' interest in reconstructing the South had waned. Northerners were beginning to tire of the attempt that Reconstruction required, were discouraged past the loftier charge per unit of continuing violence around elections, and were ready for the S to accept care of itself. All of the Southern states had created new constitutions that established universal, publicly-funded education. Groups based in the North began to redirect their money toward universities and colleges founded to educate African-American leaders.[ citation needed ]

Teachers [edit]

Written accounts by northern women and missionary societies resulted in historians' overestimating their influence, writing that nigh Bureau teachers were well-educated women from the North, motivated past faith and abolitionism to teach in the South. In the early 21st century, new research has found that half the teachers were southern whites; one-third were blacks (mostly southern), and ane-sixth were northern whites.[20] Few were abolitionists; few came from New England. Men outnumbered women. The salary was the strongest motivation except for the northerners, who were typically funded past northern organizations and had a humanitarian motivation. As a group, the black cohort showed the greatest commitment to racial equality; and they were the ones most likely to remain teachers. The school curriculum resembled that of schools in the north.[21]

Colleges [edit]

The edifice and opening by the AMA and other missionary societies of schools of higher learning for African Americans coincided with the shift in focus for the Freedmen'south Aid Societies from supporting an uncomplicated teaching for all African Americans to enabling African-American leaders to gain high schoolhouse and college educations. Some white officials working with African Americans in the South were concerned virtually what they considered the lack of a moral or financial foundation seen in the African-American community and traced that lack of foundation dorsum to slavery.

Mostly, they believed that Blacks needed help to enter a free labor marketplace and rebuild a stable family life. Heads of local American Missionary Associations sponsored various educational and religious efforts for African Americans. Later on efforts for college education were supported past such leaders as Samuel Chapman Armstrong of the Hampton Establish and Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Constitute (from 1881). They said that black students should be able to go out home and "live in an atmosphere conducive not but to scholarship but to culture and refinement".[22]

About of these colleges, universities and normal schools combined what they believed were the best fundamentals of a college with that of the habitation, giving students a basic structure to build acceptable practices of upstanding lives. At many of these institutions, Christian principles and practices were also part of the daily regime.

Educational legacy [edit]

Despite the untimely dissolution of the Freedman's Agency, its legacy influenced the of import historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), which were the primary institutions of higher learning for blacks in the South through the decades of segregation into the mid-20th century. Under the direction and sponsorship of the Bureau, together with the American Missionary Clan in many cases, from approximately 1866 until its termination in 1872, an estimated 25 institutions of higher learning for black youth were established.[23] The leaders amongst them continue to operate as highly ranked institutions in the 21st century and have seen increasing enrollment.[24] (Examples of HBCUs include Howard University, St. Augustine's College, Fisk Academy, Johnson C. Smith University, Clark Atlanta Academy, Dillard Academy, Shaw University, Virginia Marriage University, and Tougaloo Higher).

As of 2009[update], there be approximately 105 HBCUs that range in telescopic, size, system, and orientation. Under the Education Act of 1965, Congress officially defined an HBCU as "an institution whose master missions were and are the education of Black Americans". HBCUs graduate over 50% of African-American professionals, 50% of African-American public school teachers, and 70% of African-American dentists. In addition, 50% of African Americans who graduate from HBCUs pursue graduate or professional degrees. One in three degrees held by African Americans in the natural sciences, and half the degrees held past African Americans in mathematics, were earned at HBCUs.[25] [ full citation needed ]

Perhaps the best known of these institutions is Howard University, founded in Washington, D.C., in 1867, with the help of the Freedmen'due south Bureau. It was named for the commissioner of the Freedmen'south Bureau, General Oliver Otis Howard.[26] [ full citation needed ]

Church establishment [edit]

After the Civil War, control over existing churches was a contentious issue. The Methodist denomination had split into regional associations in the 1840s prior to the war, as had the Baptists, when Southern Baptists were founded. In some cities, Northern Methodists seized control of Southern Methodist buildings. Numerous northern denominations, including the independent blackness denominations of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and African Methodist Episcopal Zion, sent missionaries to the Southward to aid the freedmen and plant new congregations. Past this fourth dimension the independent black denominations were increasingly well organized and prepared to evangelize to the freedmen. Inside a decade, the AME and AME Zion churches had gained hundreds of thousands of new members and were rapidly organizing new congregations.[27]

Even before the state of war, blacks had established contained Baptist congregations in some cities and towns, such equally Silver Bluff and Charleston, Due south Carolina; and Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia. In many places, especially in more rural areas, they shared public services with whites. Often enslaved blacks met secretly to conduct their own services away from white supervision or oversight.[27] After the war, freedmen generally withdrew from the white-dominated congregations of the Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian churches in order to exist free of white supervision. Inside a short time, they were organizing black Baptist country associations and organized a national clan in the 1890s.

Northern mission societies raised funds for state, buildings, teachers' salaries, and bones necessities such as books and article of furniture. For years they used networks throughout their churches to heighten coin for freedmen's education and worship.[28]

Continuing insurgency [edit]

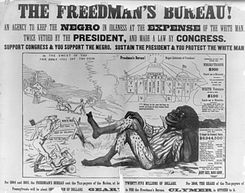

An 1866 poster attacking the Freedmen's Agency.

Nearly of the assistant commissioners, realizing that African Americans would not receive fair trials in the civil courts, tried to handle black cases in their ain Bureau courts. Southern whites objected that this was unconstitutional. In Alabama, the Bureau commissioned state and canton judges every bit Bureau agents. They were to attempt cases involving blacks with no distinctions on racial grounds. If a judge refused, the Freedmen'southward Bureau could institute martial law in his commune. All but 3 judges accepted their unwanted commissions, and the governor urged compliance.[29]

Perhaps the near hard region reported past the Freedmen's Agency was Louisiana'south Caddo and Bossier parishes in the northwest role of the state. Information technology had not suffered wartime devastation or Marriage occupation, simply white hostility was high against the black majority population. Well-pregnant Agency agents were understaffed and weakly supported by federal troops, and found their investigations blocked and potency undermined at every turn by recalcitrant plantation owners. Murders of freedmen were common, and white suspects in these cases were non prosecuted. Bureau agents did negotiate labor contracts, build schools and hospitals, and aid freedmen, but they struggled confronting the violence of the oppressive environment.[thirty]

In addition to internal parish bug, this surface area was reportedly invaded by insurgents from Arkansas, described as Desperadoes by the Bureau amanuensis in 1868.[31] In September 1868, for example, whites arrested and bedevilled 21 blacks defendant of planning an insurrection in Bossier Parish. Henry Jones, accused of being the leader of the purported insurrection, was shot and left to burn down by whites, only he survived, desperately hurt. Other freedmen were killed or driven from their land by Arkansas Desperadoes.[31] Whites were broken-hearted nearly their power as blacks were to receive the franchise, and tensions were ascent over state utilise. In early October, blacks arrested 2 whites from Arkansas "defendant of being part of a mob ... that killed several Negroes." The agent reported 14 blacks had been killed in this incident, then said that another eight to ten had been killed by the same Desperadoes. Blacks were reported to accept killed the two white men in the altercation.[31] The whites' Arkansas friends and local whites went on a rampage against blacks in the surface area, resulting in more than 150 blacks being killed.[32] [31]

In March 1872, at the request of President Ulysses Due south. Grant and the Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano, General Howard was asked to temporarily leave his duties as Commissioner of the Bureau to deal with Indian affairs in the west. Upon returning from his assignment in November 1872, General Howard discovered that the Bureau and all of its activities had been officially terminated by Congress, constructive as of June (Howard, 1907). While General Howard was dealing with Indian affairs in the west, the Freedmen's Bureau was steadily losing its support in Congress. President Johnson had opposed the Freedmen's Agency and his attitude encouraged many people, especially white Southerners, to challenge the Bureau. But insurgents showed that the state of war had not ended, as armed whites attacked black Republicans and their sympathizers, including teachers and officeholders. Congress dismantled the Bureau in 1872 due to pressure from white Southerners. The Bureau was unable to change much of the social dynamic as whites continued to seek supremacy over blacks, frequently with violence.[33]

In his autobiography, General Howard expressed swell frustration most Congress having closed downwards the bureau. He said, "the legislative action, however, was just what I desired, except that I would have preferred to close out my own Bureau and not accept another do it for me in an unfriendly manner in my absence."[34] All documents and matters pertaining to the Freedmen's Bureau were transferred from the office of General Howard to the War Section of the United states of america Congress.

Country effectiveness [edit]

Alabama [edit]

The Bureau began distributing rations in the summertime of 1865. Drought conditions resulted in then much demand that the state established its own Office of the Commissioner of the Destitute to provide additional relief. The two agencies coordinated their efforts starting in 1866. The Bureau established depots in eight major cities. Counties were allocated aid in kind each month based on the number of poor reported. The counties were required to provide transportation from the depots for the supplies. The ration was larger in winter and spring, and reduced in seasons when locally grown food was available.

In 1866, the depot at Huntsville provided five g rations a day. The food was distributed without regard to race. Corruption and corruption was so cracking that in October 1866, President Johnson ended in-kind aid in that state. One hundred xx thousand dollars was given to the state to provide relief to the end of Jan 1867. Aid was ended in the state. Records show that by the end of the plan, four times as many White people received aid than did Black people.[35]

Florida [edit]

The Florida Bureau was assessed to be working effectively. Thomas Ward Osborne, the assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Agency for Florida, was an astute politician who collaborated with the leadership of both parties in the state. He was warmly praised past observers on all sides.[36] [37]

Georgia [edit]

The Agency played a major role in Georgia politics.[38] It was especially active in setting up, monitoring, and enforcing labor contracts for both men and women.[39] Information technology also set up a new organisation of healthcare for the freedmen.[40] Although a majority of the agency's relief rations went to freedpeople, a large number of whites besides benefited. In Georgia, poor whites received nearly ane-fifth of the Bureau'due south rations.[41]

N Carolina [edit]

In North Carolina, the bureau employed: ix contract surgeons, at $100 per calendar month; 26 hospital attendants, at boilerplate pay each per month $xi.25; 18 civilian employees, clerks, agents, etc., at an average pay per month of $17.20; four laborers, at an average pay per month of $11.90; enlisted men are detailed as orderlies, guards, etc., past commanding officers of the different military posts where officers of the Bureau are serving.[42]

Some misconduct was reported to the bureau main office that bureau agents were using their posts for personal gains. Colonel Due east. Whittlesey was questioned but said he was not involved in nor knew of anyone involved in such activities. The bureau exercised what whites believed were capricious powers: making arrests, imposing fines, and inflicting punishments. They were considered to exist disregarding the local laws and specially the statute of limitations. Their activities resulted in resentment among whites toward the federal authorities in general. These powers invoked negative feelings in many southerners that sparked many to want the agency to go out. In their review, Steedman and Fullerton repeated their conclusion from Virginia, which was to withdraw the Bureau and turn daily operations over to the armed forces.[43]

Southward Carolina [edit]

In South Carolina, the bureau employed, nine clerks, at average pay each per calendar month $108.33, one rental agent, at monthly pay of $75.00, 1 clerk, at monthly pay of $l.00, one storekeeper, at monthly pay of $85.00, one counselor, at monthly pay of $125.00, i superintendent of instruction, at monthly pay of $150.00, one printer, at monthly pay of $100.00, one contract surgeon, at monthly pay of $100.00, xx-5 laborers, at boilerplate pay per calendar month $xix.20.

Full general Saxton was head of the bureau operations in South Carolina; he was reported by Steedman and Fullerton to have fabricated so many "mistakes and blunders" that he made matters worse for the freedmen. He was replaced by Brigadier General R.Thousand. Scott. Steedman and Fullerton described Scott every bit energetic and a competent officer. It appeared that he took not bad pains to plow things around and correct the mistakes fabricated by his predecessors.

The investigators learned of reported murders of freedmen by a band of outlaws. These outlaws were thought to be people from other states, such as Texas, Kentucky and Tennessee, who had been function of the rebel army (Ku Klux Klan chapters were similarly started by veterans in the starting time years after the war.) When citizens were asked why the perpetrators had not been arrested, many answered that the Bureau, with the support of the military, had the primary authority.[43]

In certain areas, such every bit the Bounding main Islands, many freedmen were destitute. Many had tried to cultivate the state and began businesses with little to no success in the social disruption of the period.[44]

Texas [edit]

Suffering much less damage in the state of war than some other Deep South states, Texas became a destination for some 200,000 refugee blacks from other parts of the S, in addition to 200,000 already in Texas. Slavery had been prevalent merely in East Texas, and some freedmen hoped for the chance of new types of opportunity in the lightly populated but booming state. The Bureau'due south political role was key, equally was close attending to the need for schools.[45] [46] [47]

Virginia [edit]

The Freedmen'south Agency had 58 clerks and superintendents of farms, paid average monthly wages $78.fifty; 12 assistant superintendents, paid boilerplate monthly wages 87.00; and 163 laborers, paid average monthly wages eleven.75; as personnel in the state of Virginia. Other personnel included orderlies and guards.[43]

During the war, slaves had escaped to Union lines and forts in the Tidewater, where contraband camps were established. Many stayed in that surface area after the war, seeking protection near the federal forts. The Bureau fed ix,000 to x,000 blacks a calendar month over the wintertime, explaining:

- "A majority of the freedmen to whom this subsistence has been furnished are undoubtedly able to earn a living if they were removed to localities where labor could be procured. The necessity for issuing rations to this class of persons results from their accumulation in large numbers in certain places where the land is unproductive and the demand for labor is limited. As long as these people remain in the present localities, the civil authorities decline to provide for the able-bodied, and are unable to intendance for the helpless and destitute amongst them, attributable to their great number and the fact that very few are residents of the counties in which they take congregated during the state of war. The necessity for the relief extended to these people, both able-bodied and helpless, by the Authorities, volition continue equally long every bit they remain in their present condition, and while rations are issued to the able-bodied they will not voluntarily alter their localities to seek places where they tin can procure labor.'[48]

Bureau records [edit]

In 2000, the U.South. Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau Preservation Act, which directed the National Archivist to preserve the extensive records of the Bureau on microfilm, and work with educational institutions to index the records.[49] In add-on to those records of the Bureau headquarters, assistant commissioners, and superintendents of instruction, the National Archives now has records of the field offices, marriage records, and records of the Freedmen'due south Co-operative of the Adjutant General on microfilm. They are beingness digitized and made bachelor through online databases. These constitute a major source of documentation on the operations of the Bureau, political and social atmospheric condition in the Reconstruction Era, and the genealogies of freedpeople.[50] [51] [a] The Freedmen'southward Bureau Projection[53] (announced on June 19, 2015) was created as a ready of partnerships between FamilySearch International and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Guild (AAHGS), and the California African American Museum. Tens of thousands of volunteers are needed to make these records searchable online. No specific time delivery is required, and anyone may participate. Volunteers simply log on (http://www.discoverfreedmen.org/), pull up as many scanned documents equally they like, and enter the names and dates into the fields provided. In one case published, data for millions of African Americans will exist accessible, assuasive families to build their family copse and connect with their ancestors. Equally of Feb 2016, the projection was 51% complete.

In October 2006, Virginia governor Tim Kaine appear that Virginia would be the outset state to alphabetize and digitize Freedmen'southward Bureau records.[54]

Meet also [edit]

- United states House Commission on Freedmen's Affairs

- Freedmen's Savings Bank

- 40 acres and a mule

- Freedmen'southward Cemetery Chalmette, Louisiana

Bibliography [edit]

- see also Reconstruction: Bibliography

General [edit]

- Bentley George R. A History of the Freedmen'south Bureau (1955); old fashioned overview

- Carpenter, John A.; Sword and Olive Co-operative: Oliver Otis Howard (1999); total biography of Agency leader

- Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American Due south after the Ceremonious War (2005)

- Cimbala, Paul A. and Trefousse, Hans L. (eds), The Freedmen'southward Bureau: Reconstructing the American South Afterwards the Civil War. 2005; essays by scholars.

- Colby, I. C. (1985). "The Freedmen's Bureau: From Social Welfare to Segregation". Phylon. 46 (3): 219–230. doi:10.2307/274830. JSTOR 274830.

- W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, The Freedmen's Agency (1901). Archived October xix, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).[ full citation needed ]

- Goldberg, Republic of chad Alan. Citizens and Paupers: Relief, Rights, and Race, from the Freedmen's Bureau to Workfare (2007) compares the Agency with the WPA in the 1930s and welfare today extract and text search

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery, 1979.[ total citation needed ]

- McFeely, William Southward. Yankee Stepfather: General O.O. Howard and the Freedmen (1994); biography of Bureau'due south caput. excerpt and text search

Education [edit]

- Abbott, Martin. "The Freedmen's Bureau and Negro Schooling in Southward Carolina," South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 57#2 (Apr., 1956), pp. 65–81 in JSTOR

- Anderson, James D. The Instruction of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (1988).

- Butchart, Ronald E. Northern Schools, Southern Blacks, and Reconstruction: Freedmen'southward Pedagogy, 1862–1875 (1980).

- Crouch, Barry A. "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Carmine, the Army, and the Freedmen's Bureau" Louisiana History 1997 38(3): 287–308. ISSN 0024-6816.

- Goldhaber, Michael (1992). "A Mission Unfulfilled: Freedmen's Education in Northward Carolina, 1865–1870". Journal of Negro History. 77 (4): 199–210. doi:10.2307/3031474. JSTOR 3031474. S2CID 141705550.

- Hornsby, Alton. "The Freedmen's Bureau Schools in Texas, 1865–1870," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 76#4 (April, 1973), pp. 397–417 in JSTOR

- Jackson, L. P. "The Educational Efforts of the Freedmen'due south Bureau and Freedmen's Aid Societies in South Carolina, 1862–1872," The Journal of Negro History (1923), vol viii#1, pp 1–xl. in JSTOR

- Jones, Jacqueline. Soldiers of Lite and Honey: Northern Teachers and Georgia Blacks, 1865–1873 (1980).

- Morris, Robert C. Reading, 'Riting, and Reconstruction: The Teaching of Freedmen in the South, 1861–1870 (1981).

- Myers, John B. "The Educational activity of the Alabama Freedmen During Presidential Reconstruction, 1865–1867," Periodical of Negro Educational activity, Vol. 40#ii (Jump 1971), pp. 163–171 in JSTOR

- Parker, Marjorie H. "Some Educational Activities of the Freedmen'due south Bureau," Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 23#1 (Winter, 1954), pp. 9–21. in JSTOR

- Richardson, Joe M. Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861–1890 (1986)

- Richardson, Joe Chiliad. "The Freedmen's Bureau and Negro Education in Florida," Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 31#4 (Fall, 1962), pp. 460–467. in JSTOR

- Span, Christopher 1000. "'I Must Learn At present or Not at All': Social and Cultural Uppercase in the Educational Initiatives of Formerly Enslaved African Americans in Mississippi, 1862–1869," The Journal of African American History, 2002, pp. 196–222.

- Tyack, David, and Robert Lowe. "The Constitutional Moment: Reconstruction and Black Education in the S," American Periodical of Education, Vol. 94#2 (February 1986), pp. 236–256 in JSTOR

- Williams, Heather Andrea; "'Wearable Themselves in Intelligence': The Freedpeople, Schooling, and Northern Teachers, 1861–1871", The Periodical of African American History, 2002, pp. 372+.

- Williams, Heather Andrea. Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Liberty (2006). online edition

Specialized studies [edit]

- Bethel, Elizabeth . "The Freedmen'southward Bureau in Alabama," Journal of Southern History Vol. 14, No. i, (February 1948) pp. 49–92 in JSTOR.

- Bickers, John Yard. "The Power to Practise What Manifestly Must Be Done: Congress, the Freedmen's Bureau, and Ramble Imagination", Roger Williams University Law Review, Vol. 12, No. 70, 2006 online at SSRN.

- Cimbala, Paul A. "On the Front Line of Freedom: Freedmen's Bureau Officers and Agents in Reconstruction Georgia, 1865–1868," Georgia Historical Quarterly 1992 76(3): 577–611. ISSN 0016-8297.

- Cimbala, Paul A. Under the Guardianship of the Nation: the Freedmen'due south Agency and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865–1870 (1997).

- Click, Patricia C. Time Total of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, 1862–1867 (2001).

- Hunker, Barry. The Freedmen'south Bureau and Black Texans (1992).

- Hunker; Barry A. "The 'Chords of Dear': Legalizing Blackness Marital and Family Rights in Postwar Texas," The Periodical of Negro History, Vol. 79, 1994.

- Downs, Jim. Ill from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 2012)

- Durrill, Wayne K. "Political Legitimacy and Local Courts: 'Politicks at Such a Rage' in a Southern Community during Reconstruction," in Journal of Southern History, Vol. 70 #3, 2004 pp. 577–617.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. "'Are They Not in Some Sorts Vagrants?' Gender and the Efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau to Gainsay Vagrancy in the Reconstruction South," Georgia Historical Quarterly 2004 88(1): 25–49. ISSN 0016-8297.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Mary. Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Agency: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (Fordham University Press, 2010); describes how freedwomen found both an ally and an enemy in the Bureau.

- Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Future: the Freedmen's Agency in Arkansas, 1865–1869 (1996).

- Lieberman, Robert C. "The Freedmen's Bureau and the Politics of Institutional Construction," Social Scientific discipline History 1994 18(3): 405–437. ISSN 0145-5532.

- Lowe, Richard (1993). "The Freedman's Bureau and Local Black Leadership". Journal of American History. 80 (3): 989–998. doi:ten.2307/2080411. JSTOR 2080411.

- Morrow Ralph Ernst. Northern Methodism and Reconstruction (1956)

- May J. Thomas. "Continuity and Change in the Labor Program of the Marriage Army and the Freedmen's Bureau," Civil State of war History 17 (September 1971): 245–54.

- Oubre, Claude F. Forty Acres and a Mule. (1978).

- Pearson, Reggie L. "'There Are Many Sick, Feeble, and Suffering Freedmen': the Freedmen's Bureau'south Wellness-care Activities During Reconstruction in North Carolina, 1865–1868," North Carolina Historical Review 2002 79(ii): 141–181. ISSN 0029-2494 .

- Richter, William L. Overreached on All Sides: The Freedmen'southward Bureau Administrators in Texas, 1865–1868 (1991).

- Rodrigue, John C. "Labor Militancy and Black Grassroots Political Mobilization in the Louisiana Saccharide Region, 1865–1868" in Journal of Southern History, Vol. 67 #1, 2001, pp. 115–45.

- Schwalm, Leslie A. "'Sugariness Dreams of Liberty': Freedwomen'southward Reconstruction of Life and Labor in Lowcountry South Carolina," Journal of Women'southward History, Vol. ix #1, 1997 pp. 9–32.

- Smith, Solomon 1000. "The Freedmen's Bureau in Shreveport: the Struggle for Command of the Red River Commune," Louisiana History 2000 41(4): 435–465. ISSN 0024-6816.

- Williamson, Joel. Subsequently Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861–1877 (1965).

- Freedmen's Bureau in Texas, Texas Handbook of History online

Chief sources [edit]

- Berlin, Ira, ed. Costless at Concluding: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (1995)

- Howard, O.O. (1907). Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard/ Major Full general United states of america Army (Volume 2). New York: The Baker & Taylor Company.

- Rock, William. "Bitter Freedom:" William Stone'due south Record of Service in the Freedmen's Bureau, edited past Suzanne Stone Johnson and Robert Allison Johnson (2008), memoir past white Agency official

- Minutes of the Freedmen'south Convention, Held in the City of Raleigh, Northward Carolina, October, 1866

- Freedmen's Agency Online

- Reports and Speeches Archived August five, 2020, at the Wayback Auto

- General Howard's study for 1869: The House of Representatives, Forty-first Congress, second session[ failed verification ]

Notes [edit]

- ^ For admission and inquires about the use of the records, researchers should visit or write (e-mail) the Old Military and Ceremonious Co-operative, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408. For the location of previously filmed and future Freedmen's Bureau microfilm publications, researchers should contact the nearest regional athenaeum or visit the NARA online microfilm catalog. By 2014, under organisation with the National Archives, records are available online through FamilySearch[52] and Ancestry.

References [edit]

- ^ A Century of Code for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved on 2016-08-01.

- ^ "Freedmen'southward Bureau Bill". Us Congress. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ Reconstruction - America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, Eric Foner

- ^ Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1

- ^ a b c d Richard Wormser, "Jim Crow Stories: Freedmen's Bureau", The Ascent and Fall of Jim Crow, 2002, PBS; Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- ^ Kelley, Robin D. G. (2002). Freedom Dreams. Boston: Buoy Press. p. 116.

- ^ a b c Clayborne Carson, Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary B. Nash, The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans, 256.

- ^ The Civil War: A Visual History. DK Publishing. 2015. pp. 338–. ISBN978-1-4654-4065-5.

- ^ National Park Service, The Freedman's Bureau Bill

- ^ Richard D. deShazo (2018). The Racial Dissever in American Medicine: Black Physicians and the Struggle for Justice in Health Care. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 35–. ISBN978-1-4968-1769-3.

- ^ Leslie M. Alexander; Walter C. Rucker (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 777–. ISBN978-ane-85109-769-2.

- ^ Tracey Baptiste (2015). The Ceremonious State of war and Reconstruction Eras. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 48. ISBN978-1-68048-041-2.

- ^ Pearson 2002; Jim Downs, Sick from Liberty: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Ceremonious War and Reconstruction (NY: Oxford U.P., 2012)

- ^ Farmer-Kaiser, Mary (2004). "'Are they not in some sorts vagrants?': Gender and the Efforts of the Freedmen's Bureau to Gainsay Vagrancy in the Reconstruction South". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 88 (1): 25–49. Retrieved Feb 19, 2018.

- ^ Farmer-Kaiser, 2004

- ^ Crouch 1997

- ^ Westward, Earle H. (1982). "Volume review of Freedmen'southward Schools and Textbooks". 51: 165–167. JSTOR 2294682.

- ^ McPherson, p. 450

- ^ Goldhaber 1992. p. 207

- ^ Ronald E. Butchart, Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861–1876 (2010)

- ^ Michelle A. Krowl, "Review of Butchart, Ronald E., Schooling the Freed People: Instruction, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861–1876 ", H-SAWH, H-Internet Reviews. September, 2011.

- ^ Morris, 1981, p. 160.

- ^ Howard, 1907

- ^ Noah Weiland, "Howard University Stares Downwards Challenges, and Difficult Questions on Black Colleges", New York Times, 26 April 2018

- ^ Data from United Negro College Fund.

- ^ Harrison, Robert (February 1, 2006). "Welfare and Employment Policies of the Freedmen'south Bureau in the District of Columbia". Journal of Southern History. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved Jan 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Church building in the Southern Black Customs". Documenting the South. University of North Carolina, 2004. Retrieved January fifteen, 2009.

- ^ Morrow 1954

- ^ Foner 1988

- ^ Smith 2000

- ^ a b c d "Parishes of Bossier and Caddo" Synopsis of Murder &c. Committed in Parishes of Caddo and Bossier September and October 1868", The Freedmen's Bureau Online; accessed 6 May 2018

- ^ Burton, Wilie. On the Black Side of Shreveport: A History (1983; 2d edition, 1993)

- ^ PBS. "Freedmen's Agency". PBS. PBS Public Dissemination Service. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Howard, 1907, 447.

- ^ Flynt, Wayne (1989). Poor But Proud: Alabama's Poor Whites. Birmingham: Academy of Alabama Press.

- ^ Joe M. Richardson, "An Evaluation of the Freedmen's Bureau in Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly (1963) 41#iii pp. 223–238 in JSTOR

- ^ Bentley, George R. (1949). "The Political Action of the Freedmen's Bureau in Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. 28 (one): 28–37. JSTOR 30138730.

- ^ Paul A. Cimbala, Nether the Guardianship of the Nation: the Freedmen's Agency and the Reconstruction of Georgia, 1865–1870 (Academy of Georgia Press, 2003); For an online review see John David Smith, "'The Piece of work It Did Not Do Considering It Could Not': Georgia and the 'New' Freedmen's Bureau Historiography," Georgia Historical Quarterly (1998) pp: 331–349. in JSTOR

- ^ Sara Rapport, "The Freedmen's Agency equally a Legal Amanuensis for Blackness Men and Women in Georgia: 1865–1868," Georgia Historical Quarterly (1989): 26–53. in JSTOR

- ^ Todd L. Savitt, "Politics in Medicine: The Georgia Freedmen's Bureau and the Organization of Health Care, 1865–1866," Civil State of war History 28.ane (1982): 45–64. Project MUSE Online

- ^ Hatfield, Edward (July 1, 2009). "Freedmen's Bureau". New Georgia Encyclopedia . Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ The United States Army and Navy Periodical and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces. Regular army and Navy Journal Incorporated. 1865. p. 616. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c come across "Reports of Generals Steedman and Fullerton on the status of the Freedmen'southward Bureau in the Southern States"

- ^ Charles F. Kovacik, and Robert E. Bricklayer. "Changes in the South Carolina Body of water Island Cotton fiber Industry," Southeastern Geographer (1985) 25#two pp: 77–104.

- ^ Claude Elliott, "The Freedmen's Bureau in Texas." Southwestern Historical Quarterly (1952): one–24. in JSTOR

- ^ William Lee Richter, Overreached on all sides: the Freedmen's Bureau Administrators in Texas, 1865–1868 (Texas A&Chiliad University Press, 1991)

- ^ Barry A. Crouch, The Freedmen'southward Bureau and Blackness Texans (University of Texas Press, 2010)

- ^ from "Reports of Generals Steedman and Fullerton on the condition of the Freedmen's Bureau in the Southern States", date

- ^ 114 Stat. 1924 [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ "African American Records: Freedmen's Bureau". August 15, 2016.

- ^ Reginald Washington, "Sealing the Sacred Bonds of Holy Matrimony/ Freedmen'due south Bureau Matrimony Records", Prologue Magazine, Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1.

- ^ "United States Freedmen's Bureau Marriages", FamilySearch Historical Records.

- ^ "Freedmen's Agency Project". www.discoverfreedmen.org.

- ^ Cheney, Catherine (July 23, 2009). "Bringing Their Lives To Light: Virginia'southward Online Records Aid Blacks ID Ancestors". Washington Post.

External links [edit]

- Freedmen'southward Bureau Online

- "Freedmen'due south Agency Marriage Records, 1815–1866", 2007, Ancestry.com website

- Joseph P. Reidy, "Slave Emancipation Through the Prism of Archives Records", Prologue Magazine, (1997)

- Georgia: Freedmen's Educational activity during Reconstruction

- Freedmen's Bureau in Georgia, New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Africana Athenaeum: Freedmen'southward Bureau Records at the USF Africana Heritage Projection

- Criminal Offenses Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Texas, Freedmen's Bureau ...Office Records, 1865–1870, Sumpter, Whorl 26, Letters sent, vol (158), June–Dec 1867, Apr–Dec 1868 .p. 112 Paradigm 60

hilliardbeirl1968.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedmen%27s_Bureau

0 Response to "what services did the freedmens bureau offer to southerners"

Post a Comment